I occasionally think about death. Being paganistic in a world dominated by the ego-centred Abrahamic faiths, my entrance into hell troubles me. May I request one thing: my arrival is accompanied by an orchestra playing my music. This should prepare me for the transition from the pangs of life to the pains of the inferno.

Here is the composition. Its structure follows eight discrete but linked sections. I think it would sound just fine in the vaults of the underworld played by an orchestra of demons, goblins and ghouls of varying nastiness:

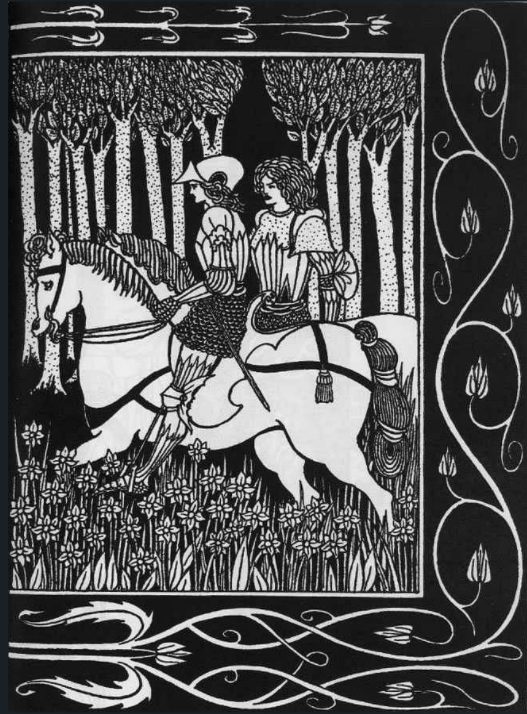

Sir Dinadan is the knight from Arthurian myth that I most identify with. He doesn’t feature heavily in the early chronicles, but is a supporting character in Tristan and Isolde, and is mentioned on numerous occasions by Thomas Malory. His encounters are characterised by battles won by accident or wit. He is a court jester – well intentioned, aware of his incompetence but unable to do anything about it.

Dinadan loves to satirise chivalry and claims he has no interest in courtly love. Romance does not inspire him in his knightly deeds, or sometime in the past love has betrayed him and he now feigns indifference towards women, or worse, fear and loathing. He’d rather be a minstrel. But a minstrel must feel to compose and relate.

Who knows from what abyss of inspiration my symphonic poem emerged. It was written over four days, about eight hours a day during the nocturnal hours – the time where my creative juices flow forth at their most plentiful. Peace pervades the night, owls sit on balconies, apartments creak and ghosts flit on the edges of sight.

The first thing I put down for Dinadan was the disjointed gyspy-like violin motif that modulates up and down a tone and underpins the first half of the composition. I didn’t have much idea at this point what this was going to develop into. I love the power and noblesse horns bring to an orchestra. So I played around with the trombones next. Brass plays a supporting role early in the composition, but their presence grows.

Clarinets and flutes enter as troubadours at 0:50, carrying a melody which derives its uniqueness from the quintuplets which divide this motif into the familiar call-response pattern. There are subtle alterations to each statement of this melody, brought about not by melodic or rhythmic variation, but by tonal variation (changing the relative volumes of the clarinet and flute parts).

Dinadan’s carefree wandering is about to end as he seeks more purpose in part C (1:20), with fanfare trumpets playing a melody in intervals of fourths and fifths. Our friendly knight senses a quest. But clouds are on the horizon. In D (1:50), the underlying four-note string pattern is still present, while murky horns signal encroaching darkness. Flute trills raise the temperature at the end of each section, the timpani sound their martial beats and the horns now dominate.

Sir Dinadan prepares for a potential duel with a dark knight sans pitié, or maybe his repressed desire is bubbling to the surface. The troubadours return in E (2:32) as Dinadan rests, raises his standard, and waits for the dawn.

Someone launches a surprise attack (F, 3:16). I doubt it’s Dinadan. He’s never ready for this sort of stuff. He grabs his lance and jumps out of his tent. The action gains momentum, the underlying string foundation plays sextuplets, a good device for chivalric and warlike music. Felix Mendelssohn is fond of sextuplets as a momentum-carrying framework. He uses them in both orchestral and piano works, examples being in the first movement of the Italian Symphony, and various Songs without Words.

Ultimately Dinadan dies, perhaps in Lancelot’s arms. The closing sequence (G, 4:15) portrays his demise in all its glory with a lofty ethereal woodwind melody over fatalistic percussion. The drums could be better; maybe I’ll ask a percussionist to redo them for me at some stage. The final nail in the coffin is increasing atonality, followed by a twelve tone row that brings Dinadan to a close. But amidst all the chivalry and adventure, it’s the journey that matters right?

You can also object to the mixing, which is very unrealistic with the overly synthesised instrumentation – I used the Logic Pro X native patches as I had yet to acquire Spitfire’s BBC Orchestra library plugin. Notice the difference in quality in a subsequent symphonic composition of mine.

So let’s say I’m in hell – here is the likely makeup of the demon orchestra, each entity assigned to instrumentation used in the composition:

Conductor: Frankenstein’s Monster

First violins: Disembodied hands

Second violins: Imps

Violas: Zombies

Cellos: Werewolves

Double basses: Vampires

Clarinets: Snakes

Flutes: Sirens

Trumpets: Money lenders

Trombones: Griffins

French Horns: Lost souls

Timpani: Ogres

Snares: Ghosts

Gong: Disembodied head

Triangle: Succubus

Chimes: Lord Byron

Read analysis of my other Arthurian composition, The Temptation of Merlin.