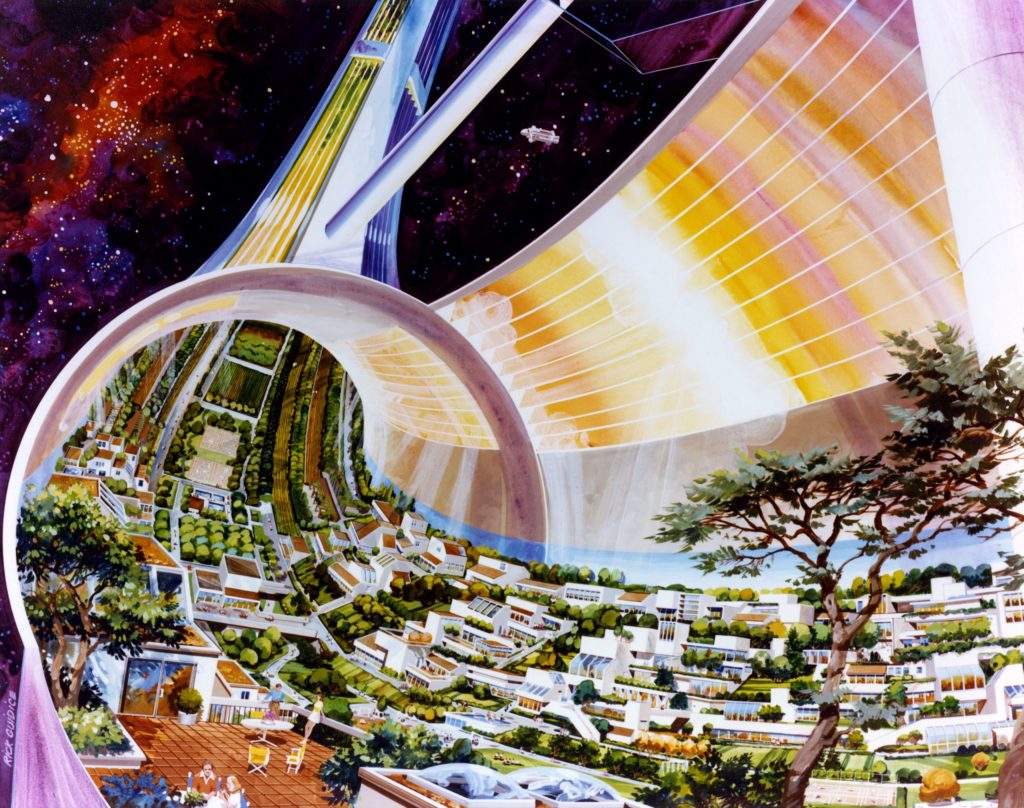

They deactivated their gravity belts as the doors of Elevator D swung open. No magnetic tiling was needed in the primary areas. Centrifugal force generated by the Eye’s rotation kept boots firmly on the ground. The force generated closely approximated Cretan gravity, or 0.94 Earth G.

Marley and Moszkowski strolled along the endlessly curving conveyor belt, past hotel suites, experimental laboratories, restaurants, and tourist stores selling fluffy toys.

They stopped when they reached an observation deck that afforded a particularly favourable view.

“It’s worth coming up here just for this,” said Moszkowski. His hand performed a wide sweep.

Marley couldn’t disagree. The space station was currently traversing the night-side of Crete. With the reddish glare of host-star Luhman 16A hidden, they had the universe before them laid out in all its glory.

The naked eye didn’t know where to look: at the vast tapestry of stars; at the Sagittarius and Scutum arms towards the bright galactic centre; or at the myriad blue and red stars that littered the sky like a teenage girl who’s discovered she can use glitter as makeup.

Moszkowski continued without looking at Marley. “It makes you feel so insignificant, yet fills you with such wonder.”

“I feel trapped here,” said Marley unthinkingly.

“I don’t blame you.” Moszkowski turned to him. “Despite all this technology, has it freed us? I work harder than ever, giving lectures and writing research papers that largely lead to mathematical cul-de-sacs. We’ve discovered so much. There must be so much more out there. But I’m just going through the motions.”

“You are, in a sense,” said Marley, “going through the planetary motions.”

“I always liked your sense of humour Chuck. I would have given you a pass if I could mark you on that.”

Moszkowski had never called him by his first name.

“I’ve lived a comfortable life. Maybe too comfortable. I should leave my comfort zone. But-”

Marley watched a blinking satellite fly by. “But what?”

“Life’s still too short. Oh, I could live another fifty years. But I’m tired, already. I need rest.”

The mere mention of fatigue made Marley yawn. “Excuse me.”

“Don’t mention it. Look, I shouldn’t give you advice. It might not be the right advice for you anyway.”

“I need all the help I can get.” Marley smiled.

“My first piece of advice then would be, keep smiling.”

Marley stopped smiling and looked out the viewplate.

“My second advice: don’t try too hard to be yourself, despite what anyone tells you. They’re just trying to box you in. You can redefine yourself at any moment.”

Marley half expected Moszkowski to grow a set of wings and soar towards the vaulted ceiling. Then he half understood what he was saying.

“Don’t be chained by life,” Moszkowski added quietly. “I don’t really know what I’m going on about. Let’s move on.”

They drew away from the observable universe outside with all its stars and galaxies and nebulae and globular clusters and rogue planets.

The conveyor hurried them past bars and casinos, showrooms, and more souvenir stores with fluffy toys.

“Let’s get off and walk.”

Moszkowski drew a four inch rod from his pocket and pressed a button on the top. It expanded into a walking stick.

“Are you sure?”

“Like my moustache, the walking stick is just for show.” He winked, and so did one side of the moustache.

The viewplates outside now showed spacecraft for sale.

A refurbished Thundercat M15, capable of single stage to orbit and intermediate solar system travel, was valued at 2 million elon or near offer. Ten times more than Marley’s loan amount.

The Arcadia Gforce advertised a new modular-magnetic plating promising to reproduce artificial gravity for long haul flights. Price tag: 3 million elon. Engineers still struggled to remake gravity using either magnetic plating or rotating habitats, like the space station they were currently inside. The Arcadia Gforce hoped to emulate the nascent cruise ship experience for private voyages.

“Bah,” said Moszkowski. “I don’t think we’ll ever solve the issue of gravity. It will always be a pipe dream. Some of the brightest minds have wasted their lives on the problem.”

“It looks pretty,” Marley admitted.

“Don’t fall in love with a shape,” Moszkowski warned.

“Don’t worry. That Arcadia is well out of my price range.”

“You have a range? I thought you lived hand to mouth.”

Marley knew Moszkowski was joking. “I got approved for a loan. A small one. But one that can possibly be enlarged should I provide a decent business case.”

“That’s the entrepreneurial spirit! I’ve always wanted to tell you, some people are better off living in the real world.” He added hastily, “Whatever that is. Don’t get me wrong, study is very important. But not if you’re not motivated. Structured formal study is not for everyone. Some personalities thrive away from the guiding hand.”

“You know me better than I know myself Professor.”

“Call me Milton.”

“Professor Milton Moszkowski, also known as Milton.” Marley almost felt like putting his arm around him.

“I would have given you this advice before, but as your Professor it would have been a conflict of interest. Moszkowski gestured around the curving corridor, then at the Arcadia. “These rotating space stations are quite livable, but adapting the technology for an interplanetary vessel is something that sends us engineers straight to the bottle.”

“Three million elon does seem a bit much,” said Marley, “This’ll need updating before long, right?”

“Probably. But people with money want their stuff to look good.”

“Even if it doesn’t work.”

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say that. But I’ve seen the specs of the Arcadia. Nothing special. It’s still magnetic field tech. Nothing special, nothing new.”

They had now reached a point in the space-station from where they could see their sun’s twin: Luhman B. They paused and entered another observation bubble.

The breathtaking scene reaffirmed Marley’s restlessness.

“I was like you,” said Moszkowski. “Wander while you can.”

“How can you lose the desire to see what’s out there.”

“Desire’s still there, means and will are lacking.”

Two meteors descended through the Cretan atmosphere. They burnt up somewhere over the Isles of Circe, the boundary of habitable Crete.

“I’d forgotten how amazing all this was,” said Marley. He remembered the school excursion, running twice around the Cretan Eye, looking through telescopes at the Pleiades and Andromeda Galaxy. If he’d known he wouldn’t return for ten years he surely would have treasured the experience more.

“We take so much for granted when we’re young.” Moszkowski tapped his cane. “They try to instill a sense of optimism into us. They have to. We permanently altered our home planet so much so that none but the rich or well-connected can live on it, or even visit there.”

“Who’d want to go there if it’s so unliveable.”

“Our ultimate place of origin, so they say. Although the Cretan system has a higher economic output, Earth is still the headquarters of the League of Worlds. Their power may be figurative in many respects, but no one wants to see the Earth fall any further.”

“Even if it means a tax on other systems.”

“You don’t pay taxes, yet. Why would you care?”

Marley shrugged his shoulders. “I want to pay taxes. Because that would mean I had a job. A job would mean purpose.”

“I’ll tell you something.” Moszkowski fingered his chin as if he wasn’t just telling Marley, but reminding himself. “These are interesting times. Our government and media is not telling us how interesting these times actually are. Do you know much history?”

Marley immediately thought of Gaston. “I never really saw the use of it. The present is all there is.”

“That’s what they’d like you to think.”

“Who’s they?”

“Good question. The powers that be. They don’t want to create undue alarm.”

“Are we in danger?”

“Another good question. I also used to live entirely in the present, thinking that was all important. I attended this lecture recently, given by an odd fellow in the history department. Associate Professor Dimble.”

“Gaston!”

“You know him?”

Marley hesitated before replying, “Not really. They say his last name used to be D’Imbroglio, but he changed it because no one could pronounce it.”

“We’re still so backward aren’t we? Anyway, I’m not sure he was aware of the full implications of his speech. It seemed to ramble from one era to another. From the Iron Age to the Tech Age to the Space Age. But I came to my own conclusions.”

Marley raised an eyebrow.

Moszkowski paused.

“I’m genuinely interested. Go on.” Marley wanted to know what exactly Gaston could say that would inspire someone.

“From Dimble’s two and a half hour lecture-”

“Two and a half hours?”

“No one had booked the Trapezium, so he just continued.”

Marley resisted the urge to laugh but resistance was futile.

Moszkowski half-smiled then continued. “Dimble keeps to himself. He doesn’t mingle with the other Professors. I pretended to be asleep, but actually his talking stimulated my thoughts. It led me to conclude that humanity only barely survived as a species 1,000 years ago. We narrowly missed one of the Fermi Paradox’s great filters.”

“Fermi Paradox? That’s the name of a drink isn’t it?”

“It’s also the name of a once influential-”

“Theory.” Marley was desperate to show Professor Moszkowski he wasn’t stupid. He’d actually heard of the Fermi Paradox, both the drink and the theory. Flippancy was his default mode in conversation. It wasn’t always in his best interests though.

“I hear you,” said Moszkowski.

“And that great filter,” said Marley, “was climate change.”

Marley was surprised that Moszkowski didn’t look surprised that he knew this.

“It was indeed climate change that made, and still makes, the Earth uninhabitable for normal people. If we hadn’t made a series of scientific breakthroughs in space travel and cis-lunar space construction, we’d have been toast. Or confined to our own planet forever, as cavemen.”

“And the Baconians would have had this sector all to themselves.”

“I don’t mind the Baconians. They’re quite like us: paranoid, expansionist.”

“And curious.”

“Which means that the Fermi Paradox didn’t turn out to be quite the paradox it was originally made out to be.” Moszkowski stroked his moustache. “Only 500 years after we went to space, we discovered the Baconians.”

“They claim to have discovered us.”